COURAGE IN THE CAGE III: Fear is a superpower

Fear makes fighters stronger, faster, tougher and even stops them bleeding

If it seems counter-intuitive - or even sacrilegious- to use words like ‘fear’ in reference to professional MMA fighters, that’s only because the nature of fear isn’t well understood.

Fear is the most primal of instincts. It has been utterly necessary to the survival of the human species. Not only does fear give us pause when we are about to do something dangerous, it can give us superpowers.

And exactly the kind of superpowers that are most useful to MMA fighters…

Subscribe today to receive each installment of Courage in the Cage (and tons of other stories) in your email inbox for free.

BROADLY SPEAKING, FEAR CAN BE THOUGHT OF AS THE SUM OF TWO twin responses to danger; one emotional/psychological and the other biochemical/physical.

There’s a precept in evolutionary biology that fear may have been the first emotion felt on Earth; that it has guided evolutionary adaption for billions of years. It was fear, this line of thought goes, that kept early mammals out of dinosaurs jaws. It was fear that stopped our human ancestors from venturing into the jungle at night. It was fear that stopped your great-great-grandfather from doing that dumb thing that would have got him killed.

Because of all that fear, you got the chance to be born.

The way we experience this most primal of emotions is highly individualized. We are all afraid of different things, to differing degrees and at different times. The biochemical/physical response, though, has been shaped at the species level over countless millennia. What our bodies do when we are fearful is the same for, well, everybody.

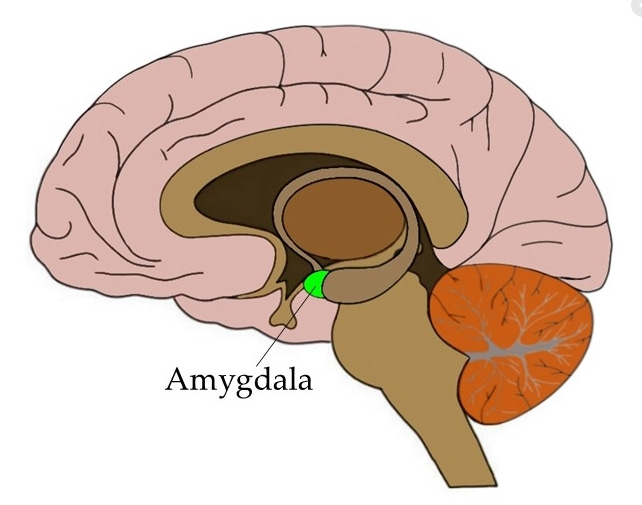

The acute stress response is triggered by an almond shaped region of our brains called the amygdala whenever we experience that we are in danger. Commonly called ‘fight or flight’, this coordinated but near-instantaneous sequence of hormonal and physiological changes lends the body ever possible cheat and advantage to fight or escape whatever danger is threatening.

For starters, the glands perched above the kidneys flood strength and speed boosting adrenaline into the bloodstream. At the same time, blood is drawn away from the skin and into the skeletal muscles, which then lock and tighten like coiled springs.

As the process continues the eyes dilate, augmenting vision.

Glucose and fat reserves are raided to boost energy levels.

The breath automatically deepens to drag more oxygen into the lungs, which are already bloated to increase capacity. The heart responds by accelerating, flushing all that extra o2 around the body. That sugar rich plasma also gushes around the brain, increasing alertness and speeding up thought processes.

All of these are advantages to any modern day athlete, but the transformation includes several benefits of particular use to professional fighters.

Ever wondered why a three inch gash over the eye of any given light heavyweight doesn’t seem to bleed nearly as much as your own shaving nick?

The answer is the acute stress response temporarily augments the blood clotting process. It sounds like something out of an X-Men movie, but the amygdala sends the body instructions to a) expect lacerations while fleeing or fighting whatever the threat is, and, b) not to bleed.

There’s more. Remember how Forrest Griffin, Rich Franklin, Paige Van Zant and others were able to continue to fight after their forearms were snapped in half?

That was possible in part because the periaqueductal gray area of their brains had been instructed to release opioid analgesia, a natural painkiller so powerful soldiers have completed missions unaware of the most horrific injuries.

And MMA fighters aren’t lying when they claim not to have heard the arena-rattling horn signaling the end of rounds. While the sense of hearing can be sharpened by fight or flight, if noise becomes a distraction the brain will switch it off as quickly and ruthlessly as if it were a Colby Covington interview.

Psychologists call this perceptual tunneling auditory exclusion.

Designed by evolution to err on the side of life-and-death emergency, the amygdala completes this work almost instantly. The threat is then evaluated by the deeper thinking hippocampus and pre-frontal cortex parts of the brain. If the threat is a false alarm or has already passed by, the parasympathetic system shuts down the fight or flight response.

But if the brain finds the danger is genuine – like an impending MMA fight, for example - the acute stress response is kicked up to the max!

Huge amounts of the hormone cortisol are released. Normal, healthy functioning is abandoned during fight or flight. Organs and functions that cannot directly assist with running away or standing and fighting are shut down, their energy snatched away by biceps or leg muscles or something else useful.

The bladder is left to its own devices (a lot of fighters make urgent trips to the bathroom before walking out to the cage). The immune system is switched off (a lot of fighters pick up colds as the fight nears).

The entire digestive system is powered down, producing that sickly “butterflies in the belly” sensation as it stutters to a halt.

And all that extra glucose racing around only adds to a nauseous, on-edge feeling, as does the increased sweating and dry-mouth. The sugar rush and sharpened sight can bring on a headache and a dizzy feeling.

Evolution designed fight or flight to help deal with imminent danger. Most MMA fights are agreed to weeks and months in advance and the anxiety only increases as the days tick by. When fight day finally arrives every fighter must try to strike a balance between being nervous enough to supercharge their body, while not becoming so fretful they handicap themselves in the cage.

Some fighters find the balancing point by first overshooting the mark; Tito Ortiz needed to physically vomit before he can calm his nerves.

“I puke every time,” Ortiz said. “Once I do it, I feel ready to fight.”

Most others prefer to siphon off excess energy with intense bursts of exercise: they hit pads or even running sprints backstage. I’ve witnessed dozens of fighters over the year, including legends like Matt Hughes and Michael Bisping, flying up and down the long grey corridors deep inside major arenas, revving their engines and willing the fight to hurry up and happen.

“You just want the fight to get here,” Bisping said.

And, a few times, I’ve seen fighters force themselves to remain so relaxed that they went into the cage without the acute stress response firing at all…

FORREST GRIFFIN WOKE UP AT THE MANDALAY BAY HOTEL, JULY 5, 2008 AS A 3-1 (+300) UNDERDOG.

The popular brawler was challenging for the UFC light heavyweight title 12 hours later, and the Las Vegas odds-makers didn’t like his chances vs the power of champion Rampage Jackson.

But Forrest wasn’t going to think about the odds. Or the predictions. And especially not Jackson’s promise to knock him flat inside the opening round. In fact, Forrest’s plan was to not think about the imminent UFC 86 main event - at all - until the hour came to go downstairs to the sold out Mandalay Bay Events Center.

“I focused on being calm,” he remembers of that Las Vegas fight day twelve summer’s ago. “I avoided thinking about the fight all day. I ate breakfast and didn’t think about it. I hung out in my room and didn’t think about it. I watched some TV and didn’t think about it. I ate some more and didn’t think about it.

“If I thought about the fight for a second, I’d think of something else (right away) - like changing the channel with a TV remote.”

Don’t tell him I told you, but Forrest is very smart and very well-read. He was well-aware of the importance of the fight or flight response long before his post-retirement job with the UFC Performance Institute .

“I knew I needed a little fear in the fight,” the Hall of Famer remembers, “but I wanted to avoid feeling butterflies in my gut all day. The idea was to save that nervous energy for the fight.”

Only, the acute stress response apparently doesn’t accept booking in advance…

Griffin said: “When it was time to get into ‘fight mode’ I was still too relaxed. I’d pushed any thought about the fight away for so long that it felt like it was months away rather than two hours.

“I felt flat. I had no energy. So I started thinking about the fight, fighting, getting hit. But my body was still ‘meh’. It was like it didn’t believe me when I said it was fight time.

“Even when I got to the arena and started warming up for my shot at the belt - there’s still no butterflies. I am hitting pads in my (locker) room, I can heard the crowd through the walls and hear guys getting knocked out - and still no nerves. No adrenaline. Nothing.

“Then I’m walking out of the dressing room into the arena, my music is playing and fans are cheering… and still nothing!

“And I’m like ‘Come on, body! Where’s the adrenaline I ordered? Send me some butterflies!’”

Forrest Griffin was moments away from the biggest fight of his life, vs perhaps the most dangerous puncher he’d faced, and his body was locked in Clark Kent mode.

He recalled: “Then the fight starts. I’m freaking out that I’m not freaked out. I’m as excited and alert as I would be doing some shopping. Then Rampage puts me down with a punch. And – boom - there’s the adrenaline I ordered! Once my body felt how hard he hit it I was in full fight mode.”

With his acute stress response now doing its work, Griffin recovered from the knockdown and a slow start to win the UFC championship on points.

“Fear is nothing for fighters to worry about,” he said. “Being afraid going into a fight is not a bad thing. Going into the cage without it once was enough for me. I was too scared to ever go into the octagon unafraid again.”

IF I COULD ASK, WOULD THOSE OF YOU READING ON THE WEBSITE PLEASE CONSIDER HITTING THE SUBSCRIBE BUTTON PLEASE? IT WILL REALLY HELP “ULTIMATE INSIDER” WITH PLACEMENT ON SUBSTACK.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS READ, CHECK OUT PREVIOUS ‘COURAGE IN THE CAGE’ ARTICLES HERE.

LOOKS LIKE EVERY ONE OF YOU HAVE ALREADY READ MY STORY ABOUT NAKED MARK COLEMAN (DICK JOKES CLICK, I GUESS) BUT FOR THE ONE OR TWO WHO HAVEN’T IT IS HERE.

FINALLY, THANKS AS EVER TO TO JEREMY BOTTER AND @MrHowardPorter FOR THE DESIGN AND ARTWORK OF THIS NEWSLETTER