TEARS FROM THE MACHINE

The heartbreak and fury of one of the all-time greatest UFC upsets

Behind Ian ‘The Machine’ Freeman's defeat of UFC heavyweight heir apparent Frank Mir at UFC 38 is a searing, heart wrenching but fundamentally cathartic tale. It is a story every MMA fan should know.

Subscribe NOW to receive The Ultimate Insider in your email inbox for FREE. Email subscribers are entered into a FREE monthly draw for signed UFC fighter collectibles.

THE EIGHTEEN-YEAR-OLD IAN FREEMAN felt the back of his head press against brick wall. The smiling thugs drew closer. They were going to hurt him, Freeman knew.

Probably hurt him very badly.

He’d tried to outrun them but in an unfamiliar neighborhood and desperate to find somewhere to flee to, to hide, to catch his breath, Freeman had taken a wrong turn down a dead-end alleyway. He was trapped. It was gone midnight. No-one would come to help.

The three men, shaven-headed and white-eyed, sneered at Freeman as they blocked his escape.

“They had sadistic grins on their faces,” Freeman remembers. “It was like a scene from a horror film. The moonlight lit up the alley in this eerie white light but their faces were all in shadow. It didn’t look like real life. I couldn’t believe it was happening to me.”

An hour before, he’d been enjoying a night out with a friend in Newcastle in England’s north east. He’d caught the last train home to his native Sunderland. He’d been making his way out of the lonely station when, across the tracks on the opposite platform, he saw a gang of skinheads kicking what appeared to be a gym bag.

Only, as Freeman’s train rumbled away into the night’s distance, he heard that ‘bag’ whimpering with every kick.

“They were just beating the shit out of this poor man,” Freeman said. “Before I could stop myself I shouted over ‘Hey! What you think you are doing?’ I was far from a tough guy, I’d never had a fight in me life. The words just came out of my mouth.”

The thugs were startled. With a parting stomp, they made their way up the stairs and out of the station. Slowly, the shape Freeman had initially thought was a sports bag drew itself up into the form of a man. The ma then limped towards Freeman to say thanks.

“He was a mess and I asked him if he needed help and he said he was okay,” Freeman remembers. “He was far from okay. He hadn’t seen what he looked like yet. He went out of the station in one direction and I went up the stairs and made my way outside to catch my bus home. It was late and I wanted to get home.”

Freeman wouldn’t make it home that night. The skinheads had waited for he outside the station.

Seeing the malice behind their eyes the teenager ran – only to be chased down and caught in the alleyway.

“They punched me to the floor and over the next god knows how long proceeded to give me the biggest kicking of me life. They took turns punching my face, kicking me in the teeth, kicking me in my back, my ribs… even when I was flat on the ground, in and out (of consciousness) in a pool of my own blood they were still stomping.”

Freeman thought the ordeal was finally over when a very large man in a bomber jacket yelled from the alleyway entrance.

“But he was another one of the group. A fat fucker who obviously couldn’t keep up with the other three when they’d chased me down. He grabbed my shirt and headbutted me. He was obviously the ringleader because he then started calling the shots.”

This larger thug, a buzz-sawed psychopath in heavy Doc Martens, mounted Freeman and laughed in his ripped open up face.

“He began head butting me. My nose broke on the first one, but he didn’t stop…”

The assault only intensified when Freeman began to vomit up balls of blood.

“They were laughing and screaming before but then they went dead silent with concentration. They were taking in big breaths of air so they could keep kicking. They weren’t going to stop.”

Knowing then his very life was in danger, Freeman dragged himself up upright and somehow staggered by the assailants. He limped into the street and - with the last of his energy - dove head first through a row of hedges.

“I had no idea what was on the other side,” he said. “It could have been a forty foot drop, a motorway, a train track… but there was at least a chance I could survive. I wasn’t going to survive if they dragged me back into that alley.”

In fact, Freeman fell about five feet and landed face down in someone’s back yard. Freeman fought to stay conscious as his attackers’ voices drew closer. After minutes of holding his breath, bleeding in the dark, Freeman realized that somehow he’d escaped.

“Whether they’d got bored, were too tired from giving me a kicking to chase me or didn’t see where I’d gone, I’ll never know,” he said.

He limped up towards the back door and thudded until lights illuminated the upstairs of the house.

“Somebody must have opened the door after a minute or two, but by then I’d lost consciousness.”

THE HORRIFIC FOUR-ON-ONE ASSAULT LEFT THE YOUNG MAN IN HOSPITAL FOR DAYS.

Freeman’s parents, Billy and Trudy, were heartbroken by what they found after rushing to their son’s side. Their son’s face was a swollen mask. Both eyes were soldered shut. He nose was pulped and ribs caved in. Fingers were broken, including the index one on the right hand which had snapped as Ian’s gold ring was taken. Deep slices around the right wrist told the story of a stolen watch.

No-one was ever charged for the appalling crime.

Three decades on, Freeman never learned who assaulted him. It was a life-changing event that struck from the dark and disappeared back into that terrible night.

In his 2004 autobiography Cage Fighter, Freeman said he fell into a deep depression. It is likely a modern social worker would treat him for PTSD, too. He let friends and interests fade from his life. He wasn’t suicidal, but he didn’t see any point in getting out of bed.

“It was a bad time,” Freeman remembers. “I really struggled with what had happened to me. I mean, psychologically, it changed me. For those cowards to take a young lad and do what they did… I was frightened to leave the house again. I was about 10stone (140lbs) and felt like I couldn’t defend myself. I was scared I’d be attacked again if I left the house. My family were worried to death about me.”

Months went by. The family bought Ian a new watch for Christmas, perhaps as a symbol better times were head.

“When I saw it, I started crying,” Freeman said. “It took me right back the when those bastards had stole the other watch from me. It wasn’t just the watch or the ring, they’d taken my confidence. My self-respect. It was like I’d been stripped of my personality.”

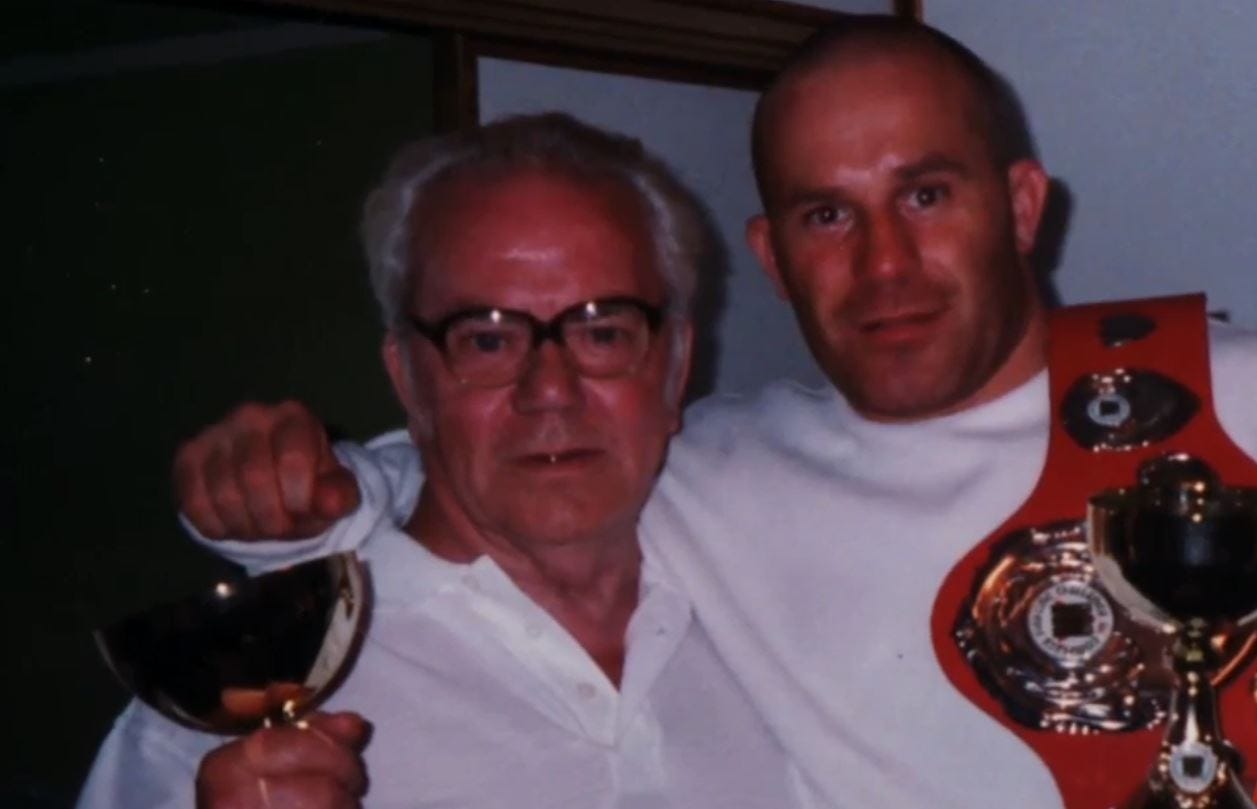

But Billy Freeman would not give up on his son. When all the encouragement in the world didn’t do the trick, the father tried a different track.

“My dad was an ABA (British national amateur) champion boxer when he was young,” Freeman said. “He’d always wanted to show me a few things but I didn’t really have an interest in fighting. And Dad never pushed it. But, about a year after the attack, he said it the only way I’d ever get back what had been taken was by fighting for it.

“He said it was time to get over it. As horrible as it was what had happened to me, Dad said, it was time to stop being afraid.”

Billy converted the spare room of their small house into a makeshift boxing gym. The ‘punching bag’ was an army surplus carry-all packed with sand and the weights were lumps of shipyard iron blow-torched into something resembling dumbbells.

It was in that room that Ian Freeman began to claw back his stolen self-esteem.

He threw himself into pumping iron and whaling away at the sandbag.

His confidence grew along with his new mass and power.

Over months and years, Freeman became a new version of himself, steely confident in his hard earned physical strength and punching power.

By the late eighties, Freeman had gone from a terrified 140lbs boy to a 220lbs man who worked as a bouncer in Sunderland’s busy nightlife scene. While he wouldn’t seek trouble out, the tank of a man wasn’t disappointed if he found some.

“I was done running away from people like that,” he said. “If someone wanted a go, we could have a go...”

One such incident came in 1989 when Freeman found himself swapping haymakers on the boozy side streets. Freeman sent the man limping away holding his jaw - but one of his Freeman’s fellow doormen wasn’t impressed.

Freeman remembers: “He goes: ‘You shouldn’t have punched that guy. You’ll damage your fists and he has marks on him if he wants to (press charges). You should have choked him out with a rear-naked.’”

Bemused as well as insulted, Freeman asked his colleague a simple question: “What are you talking about?”

And thus, Ian Freeman was introduced to martial arts. Finally, the smoldering fury he’d carried with him since the attack was allowed to catch light. More years passed, but Freeman’s passion for competitive martial arts continued to burn.

“All I wanted to do was train, workout, compete. It was my whole life and I became one of the best in the country, if not the best. Then one day someone hands me a VHS tape of something called the Ultimate Fighting Championship. I couldn’t believe what I saw. This was literally the ultimate of fighting. I knew I had to do it.”

With no clear path from the UK to the remote world of American MMA, Freeman tore up the tiny UK scene, hacking down his first six opponents in one-round each on the basketball courts of small leisure centers in outposts up and down the British motorways.

“My dad was my biggest fan,” Freeman said. “He was slightly disappointed I didn’t become a professional boxer but he came to all my fights in the UK. He was very proud. Whenever I was taken down he thought it was as bad as a knockdown in boxing, and then I’d win and he’d think I was the greatest come-from-behind fighter of all time. He really didn’t understand the groundgame at all.”

In December 1999 Freeman beat experienced American fighter Travis Fulton, who had taken the trip to the UK despite having signed a contract to join the UFC. Fulton’s golden ticket was rescinded, and the UFC offered Freeman a contract instead.

And so the first time a British fighter competed in the UFC was at UFC 24, March 10, 2000, when Ian “The Machine” Freeman faced Scott Adams in Lake Charles, Louisiana. Freeman was tapped in the first round, but came back to win his next two UFC bookings, beating Nate Schroeder and Tedd Williams at UFC 26 and UFC 27, respectively.

“Unfortunately, my dad couldn’t see the fights,” Freeman said. “We were a working class family and plane tickets to America are expensive. He couldn’t even watch me fight on TV, as the only way to see UFC fights in the UK back then was months later on VHS video.”

But in early 2002, the UFC began making noises it would be promoting its first ever event in the UK. Freeman got a call about appearing on the July 13 card.

“Finally,” Freeman remembers thinking, “My dad can see me fight in the UFC. He would be ringside, right there in the front row. We were both so excited. A fight at the Royal Albert Hall! Finally, my dad could see me fighting in a proper, big arena. I couldn’t wait to make him proud all over again.”

Freeman hoped to be matched with a striker, but instead he got the best submission fighter in the UFC.

AT JUST 23-YEARS-OLD FRANK MIR WAS THE MOST TERRIFYING YOUNG TALENT IN THE UFC.

While the 5ft 11inch Freeman had bicep curled his way into the division, the 6ft 3inches, 230lbs Mir was a natural heavyweight. The American also possessed the best submissions the division had ever seen. He was 4-0 with four subs. His two previous UFC appearances had seen him tap ADCC gold medalist Roberto Traven and former UFC title challenger Pete Williams in about sixty seconds each.

Mir was also a good talker and friends with UFC matchmaker Joe Silva. No doubt about it, the native Las Vegan was riding a rocket ship to a UFC title reign.

“I was a stepping stone,” Freeman recalled. “I was supposed to be victim number five for their poster-boy. Mir would come to England, beat me, and go back to Las Vegas for his title shot. It was all a forgone conclusion.

“I don’t blame anyone for thinking that. Mir was a huge step up. I had to be better than I’d ever been in my life, I knew that. This was my world title, my World Cup Final.”

Freeman had already spent a fortune on overseas training sojourns with the likes of Renzo Gracie but, facing Mir, the Englishman contacted reigning UFC heavyweight champion Josh Barnett.

“Josh said he’d train me in Seattle,” Freeman said, “but on one condition. If I quit in practice or gave less than one hundred percent he’d wash his hands of me. I agreed… and for over a month, twice a day and six days a week, that man absolutely murdered me.”

With only two weeks before fight time, Freeman was better fighter than he’d ever dreamed of becoming. Then a frantic phone call from England wrecked his world.

His father, Billy, had fallen seriously ill and was in an ICU.

Freeman flew home to England. By the time he reached the hospital, a devastating prognosis had been delivered. His father’s life expectancy was two months.

“There was a cancer tumor in Dad’s brain,” Freeman said, “that’s what caused the stroke. We all know we will lose our parents, but you can’t ever prepare for it. My Dad was everything to me. I don’t know if I’d have ever got over what happened to me in that attack without my dad.

“I couldn’t imagine what the world would be like without him.”

Of course, as soon as he could think straight, Freeman intended to inform the UFC he wouldn’t be competing in London. Even if he could somehow compartmentalize his grief long enough to compete, how could he leave for London for fight week and not spend those precious days at his father’s bedside?

“I just wanted to spend every second we had left with my dad. I told my mum what I was going to do (pull out of UFC 38) but she shook her head. She said ‘You’ve worked years for this - this chance won’t come again.’ But I was like ‘No, I want to be with my Dad. It is stupid anyway, there’s no way I can focus on the fight now.’

“I’ll never forget the words - this is what gave me the inspiration to go in there and just beat the shit out of Frank Mir – my Mum said, ‘Dad’s always been supportive of everything you’ve done but he is so proud you became a professional fighter. He is so proud and happy you are fighting in a huge event in London. He knows what this fight in London means, how hard you’ve worked for this.

“‘Listen, go to London, beat him up, and come home and tell Dad you’ve got him the best going away present ever.’”

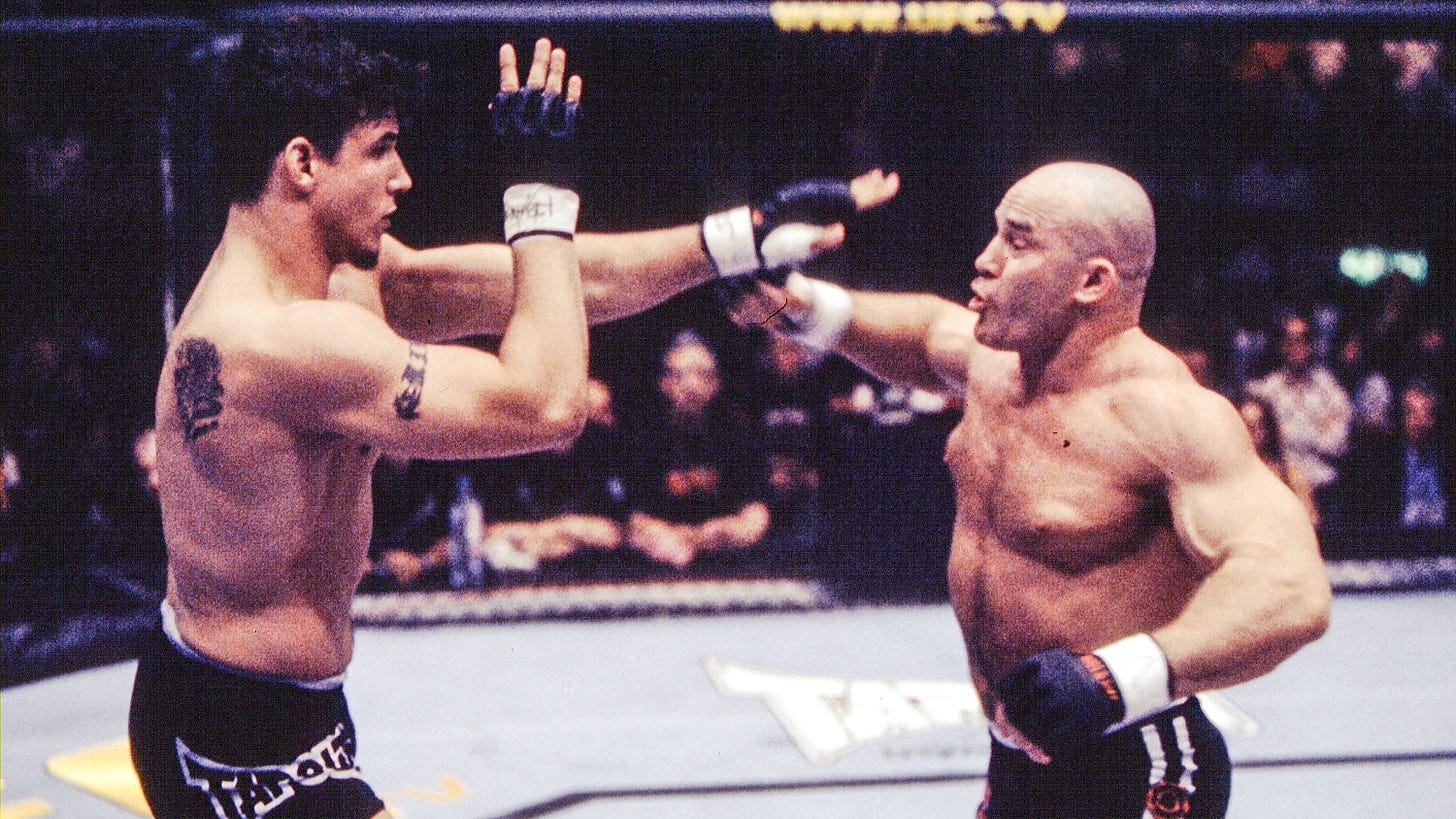

(Freeman (L) vs Mir (R) was the ‘main event’ in all but name in the UK marketing)

THREE OTHER BRITISH FIGHTERS COMPETED AT UFC 38. The main event was the hotly anticipated UFC welterweight title rematch between Matt Hughes and Carlos Newton. And yet Freeman’s fight with the heavyweight heir apparent was the most heavily promoted fight on the card.

Before he flew out to Barnett’s boot-camp, Freeman had been the centerpiece for national media attention the likes of which no US-based UFC fighter would receive for several years to come. National newspapers sent reporters to interview Freeman. He was on national radio and national television.

I covered UFC 38 for a boxing website and can report Freeman handled the attention with poise. The launch press conference at a London sports bar on March 17 was filled with journos desperate to pen “human cockfighting” pieces; while many of them still did write such guff, Freeman articulated the sport beautifully.

British MMA always seems to find the right spokesperson at the right time. That streak began with Ian Freeman.

But the added attention was both distraction and burden.

“I’ve competed all over the world and won championships, but if I lose in the first ever UFC in the UK I’ll only be known as a failure in England,” he told me a few days before the fight. “That’s a lot of pressure when you’ve been doing this out of the spotlight for as long as I have.”

At the time, I thought he was struggling with the pressure. Of course, I didn’t know the situation with his father.

“It was hard,” Freeman remembers of fight week. “Every day - many times every day - I’d think of just packing my clothes and going back home. It was only my mum’s words - giving dad the best going away present ever, making him proud of me one more time - that kept me there.”

Freeman spent much of the fight week in his room, on telephoning tears to his wife Angie, who would join best friend Carl Simpson and Josh Barnett in his corner for Saturday’s fight.

Mir, meanwhile, was as cocky as you’d expect of an undefeated 23-year-old phenom. At least on the surface. He swaggered around the fight hotel like he was in London to do a little sightseeing, but it was an act.

“I was nervous the entire time,” Mir said. “I’d barely been out of Las Vegas before, much less out of the country. I was so young and inexperienced. Not just in MMA, I was inexperienced in life. I didn’t know I needed a passport to go to England until the UFC told me and when they did I was like ‘Okay… so how do I get one of those.’”

UFC 38 took place in the Victorian splendor of the Royal Albert Hall. Completed in 1871, the Hall is held and operated in a trust in the name of the British people. Having banned boxing events several years before, the trust believed UFC was a pro-wrestling act when they accepted the UFC 38 booking. They tried to cancel the booking with just days to go when they realized their mistake but, to his credit, UFC president Dana White held them to their contract.

The atmosphere cracked as the first fight began. Partly due to the “human cockfighting” coverage, the event was a major happening in London. Impossibly attractive members of several British girl groups sat ringside, along with soccer players I paid less attention to. Supermodel Elle Macpherson was there.

“My Dad should have been there with em in the front row,” Freeman remembers thinking when it was his turn to walk to the cage.

Then the biggest fight of his professional career began.

Still managing to pretend his nerves didn’t make it through customs, Mir swaggered into a stance at the start of the first round. He began his fight with high kicks. Freeman barely looked at them as he closed the distance like a harbor shark.

“We knew Mir like to throw kicks at the start of the fight so we planned on blocking them and throwing the right cross as hard as I could,” he said. “After taking a few of those, Mir forgot all his talk of me being a great opponent to test out his stand-up on.”

The BJJ expert went for the takedown but, thanks to Josh Barnett’s beastings in Seattle, Freeman stuffed it and took top position.

“Then it was time to start hurting him,” the Briton recalled.

The term ‘scapegoat’ has slackened with use but its original meaning comes from ancient Judaism. Thousands of years ago a practice began where hands would be laid upon a goat to signify the animal absorbing all the villager's sins. The poor animal would then be driven out into the desert to die, taking the sins with it.

After crawling away with his life from that alley, Ian Freeman did something like scapegoating. Not with sin, but rage.

Anger at his nameless and long gone assailants powered every punch he stabbed into that sand bag his dad hung in that spare bedroom. That same fury fueled his passion for martial arts and at UFC 38 - with the man who rescued him from despair now dying in hospital- Ian Freeman emptied every drop of his piping hot rage into Francisco Santos Mir III.

The British heavyweight was a wild and whirling machine, slashing and hacking at the man caught beneath him.

Finally, a shell-shocked Mir sniffed a submission and torqued everything he had into a heel hook.

“That thing was vicious,” Freeman said. “Most excruciating pain of my life. I will have trouble with that leg for the rest of my life. Honestly, in a normal fight, I would have tapped. I heard my knee pop then crack and… I’ll say it now… I wanted to scream in pain. But I wasn’t going to quit. No way. No man alive could have made me quit that night.”

Years later, after I’d got to know Mir a little, I asked the by-then two-time UFC champion about that sub attempt. Mir said he readjusted the hold because, in his inexperienced mind, he was sure it must not have been executed exactly right. How else could it be that Freeman was not tapping?

That split-second Mir took to fine-tune the submission was enough for Freeman to reach forward and grab behind the Las Vegan’s head. The Briton pulled himself forward to take pressure off the lock and, gripping the base of Mir’s skull with his left hand, began bludgeoning away with his right fist.

Mir was forced to let go. Freeman escaped to his feet.

Then a roar echoed around the Victorian amphitheater: “FREE-MAN! FREE-MAN! FREE-MAN! FREE-MAN!”

“I heard it,” the British pioneer said. “It was amazing, the thrill of my life. Electric. It made me even more determined to smash this guy.”

The young Mir hadn’t wanted to be in London in the first place and now - hurt, bloody and bewildered that the ankle hold hadn’t ended the fight - he reluctantly followed Freeman to the feet. He attempted a weak takedown which only handed The Machine top position once more.

“When I passed his guard, I knew,” Freeman said. “You don’t pass Frank Mir’s guard that easy. He’d broken, mentally. The fight was mine. I took side-control and battered his face with elbows, punches, hammerfists – you name it.”

The fight was stopped at 4:35 of the first round. As the Royal Albert Hall roared, the enormity of what he’d accomplished sunk into Freeman like a stone.

“I’d won... I’d beaten Frank Mir, the next big thing, champion in waiting, the guy who was guaranteed to be the next UFC superstar,” he said as if it hadn’t lost its power to surprise. “It was one of the greatest moments of my life. It was the highest high I… I can’t describe it. I can’t do it justice, what I felt.”

In his post-fight interview in the center of the Octagon, Freeman dedicated the victory to his father Billy. The crowd hushed when their new hero revealed his dad was in a hospital bed, dying.

Freeman took a breath. “For you, Daddy. I love you.”

The winner limped to his locker room and breathlessly asked his wife to telephone home.

Her face dropped when she did.

The cancer had taken Billy Freeman the day before.

His last wish on Earth was for his son to fight at UFC 38 and have the best chance of winning.

The emotional whiplash left Freeman spinning . “I went from the elation of pure joy to just pure sadness in an instant. I was in shock. I don’t even think I cried for a while. I was just empty. I’ve never been so happy and so heartbroken within the span of two minutes.”

(FREEMAN (L) spars with MICHAEL BISPING (R) IN SEPTEMBER 2005)

FREEMAN TKO 1 MIR REMAINS ONE OF THE BIGGEST UPSETS IN MMA HISTORY (No.66 according to Tapology).

It was the highlight of The Machine’s career. Freeman lost a final eliminator to Andrei Arlovski at UFC 40 in just 85 seconds; he wasn’t over the death of his father and the will to fight simply wasn’t there. He returned for another eight fights spread over the next 11 years, winning three good championships and, even in his 40s, underlying just how good he was in his prime.

The publicity from UFC 38 helped launch him into a varied career as a TV presenter, MMA promoter, MC and commentator.

Yet his real legacy is the path he’d blazed for British MMA. Because of the Machine, there was a track from the UK to the UFC. Las Vegas, the Octagon, they both seemed so much less distant now. Whether those 3700 fans came to the Royal Albert Hall to see “human cockfighting” or not, many left as real MMA fans and formed the bedrock for everything that followed.

Within months, Cage Warriors and Cage Rage – two historically vital promotions in that part of the world – were up and running. Two years after that Freeman spent a few weeks in Nottingham training with a group of young fighters named Paul Daley, Dan Hardy and Michael Bisping. More British fighters followed. Freeman’s daughter, Kennedy, is now signed by Bellator MMA.

Freeman’s close association with Cage Rage’s brand of MMA probably hurt his chances of any sort of ambassador role with the UFC when it returned to British shores for good in 2007. That was too bad and Freeman is not as well-known today as he deserves.

Nevertheless, the fact The Machine is the first Briton to fight, to win and to score a major victory in the Octagon is there for anyone who cares to look it up. So is the entire story behind his UFC 38 win.

“I’m glad I fought at UFC 38,” he said. “I’m pleased my family didn’t tell me about my Dad passing. All I ever wanted to do, like any son does, was to make my Dad proud. I did that. It was the best fight of my entire career. I was never better as I was on that night.”

He paused for composure as a tear slide down his cheek. Then a smile wide and genuine with contentment stretched across his face.

“My Dad saw the Frank Mir fight,” he said with certainty. “He was there with me. Dad had the best seat in the house.”

(Below: Billy and Ian, the fighting Freemans)

If you enjoyed this essay, please hit the blue button below for a FREE email subscription to The Ultimate Insider. Email subscribers are entered into a FREE monthly draw for signed UFC fighter collectibles.

Check out previous articles here.